As the W16-powered era comes to a close, Bugatti ushers in a new focus on horology-inspired automobiles

Shipping Superyachts Across Oceans

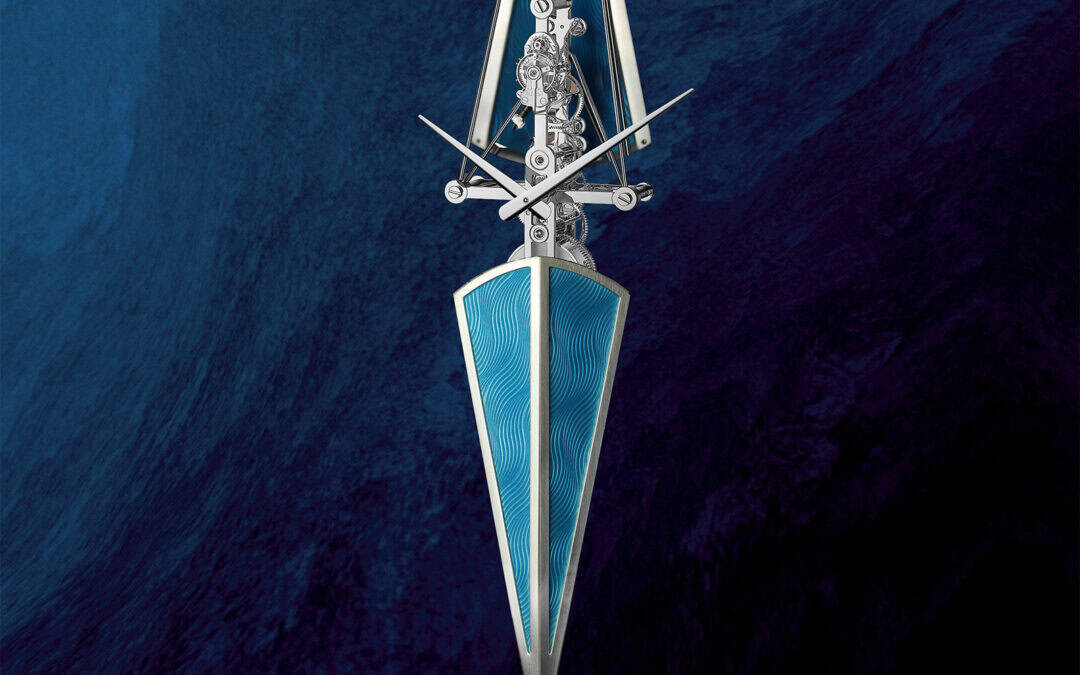

By pairing its famed hood ornament with a back-lit analog chronometer, the brand fuses century-old symbolism with modern…

A new generation of yacht clubs is making ownership optional

Three quintessentially British steeds meet two Bremont aviation watches on a cross-continent journey

Cast in “Landman” and “Yellowstone” among many others, the Bentley Continental GT Speed stars in a new iteration of ultr…

It’s a Sunday evening. M/Y Quinta Essentia, the 180-foot, six cabin vessel sits moored just outside Fort Lauderdale after a long weekend on the water. A HondaJet bound for New York is at the ready. A Ferrari F40 is part of the plan too, ready to make its appearance in Port Hercule during the Monaco Formula 1 Grand Prix. Ownership may confer access, but logistics still rule everything.

There is an entire industry built around this exact scenario. It functions as a private valet service for yachts, designed to move some of the world’s most expensive floating objects without ever turning an engine over.

Chris Perez, managing director of Peters & May USA, a global freight forwarding and courier company, told Crown & Caliber that it is a “very niche industry.” It is also far more complex than it appears.

On the surface, moving a yacht from one continent to another might seem like little more than a long journey at sea. Robert Kramer knows this well. He owns a Hampton 558, measuring 55 feet, 8 inches, and has explored shipping it several times, although a transatlantic crossing under its own power was never realistic.

“Most boats don’t carry enough fuel to go for 3,400 to 3,500 miles,” Kramer said, adding, “most boats don’t have fuel tanks that big and there’s no place to get fuel along the way.” Even if fuel were not an issue, the trip would require roughly 400 hours underway. That means engine wear, crew costs, provisions, and exposure to unpredictable conditions. “There’s a difference between tackling three-foot waves and a rapid onslaught of 12-foot waves,” Kramer said.

Anyone who watched “The Wolf of Wall Street” knows better. The infamous storm scene, where a vessel sinks amid what Jordan Belfort famously calls “some chop,” remains a useful reminder that the ocean does not care about intent or confidence.

In an era when seasonal cruising calendars, charter commitments, and global events dictate owners’ plans more than their boats’ range or seaworthiness, the choice to not sail under power has become a strategic one. Yacht transport is no longer a curiosity or luxury concession; it is a practical necessity for owners who value time, preserve mechanical life, and avoid needless risk.

This is where companies like Peters & May enter the equation. Perez said his firm ships hundreds, sometimes up to 1,000 boats per season, using fleets of specialized cargo vessels capable of carrying anywhere from 10 to 20 yachts per trip, depending on size. These ships crisscross the Atlantic, Asia, the Mediterranean, Northern Europe, and the Middle East. That count includes only vessels 40 feet or larger.

The same infrastructure also supports smaller craft. At one point, Perez said 20- and 30-foot center consoles accounted for nearly 70 percent of Peters & May business, with 20 to 30 boats shipping monthly out of Florida alone.

Yacht transport was historically seasonal. “Eastbound, which is the beginning of the year, what we are doing now, so we’ll do Fort Lauderdale, one Caribbean port, and then we’ll go to the Mediterranean,” Perez said. Stops often include Palma and Genoa before reversing course in the fall, bringing boats back to South Florida and the Caribbean. COVID and the normalization of remote work blurred those cycles. “It’s become a year-round industry,” Perez noted.

How a yacht is loaded depends entirely on size and weight. Most shipments are Lo-Lo, or lift-on, lift-off, requiring vessels with enormous crane capacity. “A lot of these boats are well over 100 tons,” Perez said, adding “if you include our rigging, our spreaders, and all that other stuff, we’re talking boats upwards of 200 to 300 tons.” In rare cases, Flo-Flo transport is used, where a cargo vessel partially submerges to allow yachts to float into position before being lifted clear of the water.

The most common yachts shipped measure between 60 and 80 feet, but relationships grow as boats do. Kramer and his wife, Suzi Saxl, progressed from a 29-footer to a 36, then a 43, before arriving at their current Hampton. Over time, customers give advance notice as their yachts grow larger, allowing logistics teams to plan accordingly.

Cost varies widely. Shipping a 70-foot Sunseeker from Fort Lauderdale to Palma de Mallorca runs about $64,000, with insurance adding roughly $13,000 according to Perez. A 104-foot Ocean Alexander bound for Genoa costs $121,135 to ship, plus $23,300 for insurance. For context, those vessels cost between $3 and $10 million. “We’re talking about a hefty chunk of change,” Perez acknowledged, “but if you think about it in comparison, it’s a $10 million boat.”

Insurance is not optional. Standard yacht coverage typically stops at ocean transport, much like auto insurance ends once a car enters a racetrack. Specialized marine shipping insurance exists precisely to cover that gap.

Perez’s advice is simple. “Do your due diligence. Go in there, vet the company. Double check the inquiry, look them up,” and “maybe talk to somebody who has shipped a boat before.” Rates that appear too low are often a warning sign. Red flags might be if a company doesn’t own their own cradling or lifting gear or rates that just seem too good to be true, Perez noted. “The industry standard is the industry standard. It’s not going to be that great a difference.”

He added that beyond Peters & May, Sevenstar Yacht Transport is the most used secondary option. Sevenstar declined to comment for this piece.

For Perez, a third-generation maritime worker with 15 years in the business, the hardest part remains persuading owners that shipping is safer than sailing. “Trust me,” he said. “It’s much safer to lift it out of the water and put it on a cargo ship than it is to take it on your own.”

For those who measure luxury not just by possession but by control, that reassurance may be the most valuable service of all.

As the W16-powered era comes to a close, Bugatti ushers in a new focus on horology-inspired automobiles

By pairing its famed hood ornament with a back-lit analog chronometer, the brand fuses century-old symbolism with modern…

A new generation of yacht clubs is making ownership optional

Three quintessentially British steeds meet two Bremont aviation watches on a cross-continent journey

Cast in “Landman” and “Yellowstone” among many others, the Bentley Continental GT Speed stars in a new iteration of ultr…