Late last summer, when the waves were small and the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Los Angeles was smooth, or “glassy,” as surfers say, something flashed brightly in the lineup. A surfer paddled wide, angling to pick off an incoming set wave in a breach of etiquette. On his wrist was a Rolex Datejust. He paddled his surfboard hard, popped up with his nose pointed down, and “pearled,” his board pitching forward into a barrel roll – largely a beginner’s mistake.

“Karma,” somebody said. If you take a wave out of turn, you’re at least expected not to waste it. The lineup of surfers, each waiting for their waves, can forgive talent, but not empty aspiration.

The “surf watch” is an unsettled category. Rolex’s Oyster case crossed the English Channel in 1927, when British athlete Mercedes Gleitze spent 10 hours swimming with one on her wrist. It can handle a summer surf session. Most collectors would agree, there’s something admirable about wearing an aquatic-rated watch in the water, despite what it may communicate about your plans for the day. Unlike diving and sailing, with their grand ties to global exploration, watches are historically absent from surf history.

Surfing never produced a crossover figure quite like Jacques Cousteau, who consulted on the orange-dial Doxa SUB 300s issued to his crew. Surf legend Duke Kahanamoku wore trunks and, sometimes, a tank top while surfing slabs of redwood and koa. Early California surfers were punks with a DIY, anti-materialist ethos. The later professionalization of the sport, accelerated by short-boarding Australians applying hydrodynamics to board design, only reinforced the idea that anything unnecessary should fall away. In surfing, the only accoutrement is the style one brings to the wave.

Yet surfers’ affection for bespoke gear – the best boards are still shaped by hand – makes them potentially natural customers for mechanical watches. With nearly 40% of the world’s 4.2 million surfers coming from six-figure households, the sport skews coastal and affluent. Luxury brands have followed the money, primarily by cross-marketing dive watches, those timepieces that are waterproof, durable, and legible, as all-purpose aquatic tools.

Kelly Slater, surfing’s most public face, has lent his name to several special editions of Breitling’s Superocean Heritage and, via his apparel label Outerknown, Vaer’s D4 Meridian. In 2021, Tudor began partnering with the World Surf League to sponsor annual big-wave challenges at Nazaré, Portugal, and Pe’ahi (Jaws), on Maui’s north shore.

Big waves require an armament of specialized equipment: narrow longboards called guns that are built to hold a line at 50 miles per hour; jet skis to tow surfers faster than they can paddle; life jackets that inflate like airbags upon impact. What they don’t require is diver certification. A rotating bezel offers little benefit to a surfer, and a 300-meter depth rating is overkill for even the awesome power that a 25-meter wave can generate.

For professional surfers, who often rely on sponsors to fund gear and airfare, this influx of brand interest has been a boon. Louche, free-spirited, and environmentally adjacent, they can present as the face of a jet-setting, death-defying lifestyle that’s also supremely cool. This past season at Nazaré, the Portuguese big wave rider Nic Von Rupp looked dashing with his Tudor Pelagos strapped over his wetsuit as he posed for the press and hoisted his trophy. The image sticks. Something about an ocean-blue, time-only watch feels surferly in its elegant simplicity.

The Breitling Superocean’s sunburst dial catches the light with an almost liquid shimmer, an effect amplified on Slater’s leaf-print edition, although the ceramic bezel dulls some of that romance. It’s a beautiful watch, evocative of a certain midcentury nostalgia that’s not uncommon in surfing. Still, for all its onion crown and broad-arrow hands, the watch feels less like a piece of equipment you’d be comfortable banging on a fiberglass board. Having paddled out (in much smaller waves) with my Black Bay 58, I can confirm having a steel watch on your wrist is an excellent way to feel self-conscious—and worried about your rails.

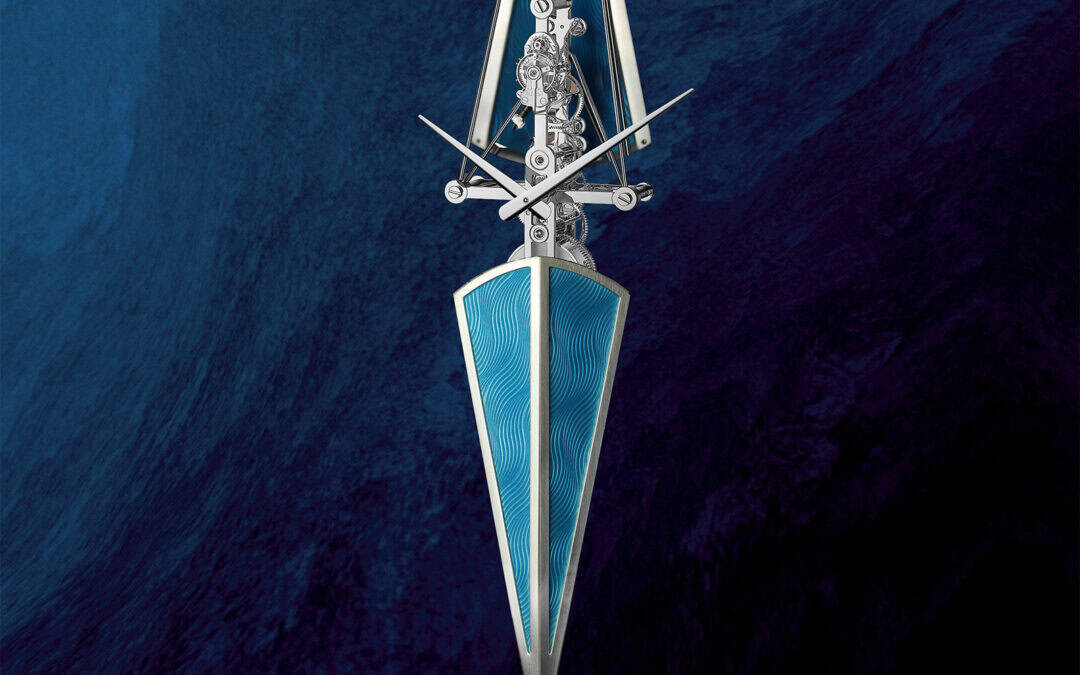

Photo: Will Fenstermaker

More often, I surf with a humble GLX-5600KB-1, one of several limited G-Shock editions designed in collaboration with Olympian Kanoa Igarashi. I love it. It’s ugly, functional, and unassuming, which satisfies the assignment, and I increasingly wear it on non-surfing days. It looks like every other resin 5600 save for a mostly decorative metal cage and Igarashi’s signature visible under illumination. It also has all the familiar functions. It fits over a wetsuit, times my sessions, and keeps me from getting parking tickets. It won’t get me mugged at a sketchy break.

The watch is ostensibly made for surfing, but it’s not the perfect surf watch. It does too much, demands too much attention. Sometimes I find myself messing with the buttons and missing a set, or trying to memorize the minutes I made a good wave or smart turn so I can check the beach cams later. Those are the days I enjoy least.

Smart devices are an increasingly common sight, alongside GoPros and drones, as surfing accessories have boomed into a massive, $4.1-billion industry, according to a Global Surfing Apparel and Accessories Market Report from MR Forecast 2023 report.

That same year, the World Surf League began issuing Apple Watches to track competitors’ scores and priority; surfers like Caio Ibelli and Leonardo Fioravanti complained they didn’t work.

but are inaccurate and error-prone. Photo: Will Fenstermaker

In 2020, Garmin launched a popular line of solar-powered fitness watches integrated with Surfline (like Strava for surfers), while apps such as Dawn Patrol track wave count and performance. The promise of helpful training data is enticing, but the software feels fiddly and inaccurate – and I don’t want an email finding me well a quarter-mile offshore. I briefly wore an Oura ring to log my sessions, but the ocean ripped that right off my finger.

The GLX-5600KB-1 does have two functions that matter to me: it shows the phases of the moon and the tidal calendar. Together, they provide a very general sense of how the waves might change and how dramatically. This is moderately useful in practice, but rich in symbolism. Adjusting either requires consulting local moon charts and lunitidal intervals, offering a subtle callback to traditional navigation, where timekeeping worked in concert with the stars, moon, and tides. Marine chronometers helped calculate longitude; tidal and lunar modules predicted the water’s movement and the shoreline’s shape.

Yachting watches better reflect that tradition, and timepieces that feature a mechanical tide complication, like the recently reissued Tag Heuer Seafarer, hold some romantic appeal to the surfer. But as a proper surf watch? Not quite. I fear its chronograph pushers would leave it vulnerable to water intake. Increasingly, I imagine the ideal surf watch as something like the Seafarer or Solunar sporting a dual moon-phase, tide-phase display. The tide is filling, the tide is draining. A clock that shows the direction of change.

Usually, one surfs to get away from time. Or to gain a different vantage on it. Surfers have developed an arcane jargon: surf can be firing, clean, peaky (good); blown-out, mushy, crumbly (bad); or flat (nonexistent). All of these words describe the convergence of oceanic and geological processes that are otherwise difficult to comprehend in real time. Ancient water clocks, or clepsydra, were thought to represent “the image of eternity in motion,” a model in which seconds and minutes lose their usefulness as fixed units.

Time becomes a bodily thing, and timing your ability to intuit the subtle rhythms of exactly how the moon and reefs, storms and currents exert force moment by moment on a fluid ecosystem. There’s no tool that can measure the shifting distance between achieving that stupid bliss of gliding in harmony with nature and getting slammed underwater, counting the seconds until you can breathe. Out in the lineup, waiting for a wave, there is nothing to count. There is only the slow churn of the horizon, the lift of the swell beneath you, and the awareness that something will come, is coming.

When it happens, you don’t need to know what time it is. You only need to be ready.