In an industry where independence is increasingly rare, L’Epée 1839 has fully embraced its new chapter. In June 2024, LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton acquired Swiza, bringing the historic Swiss clockmaker into the group’s watch division alongside Hublot and TAG Heuer. The move raised immediate questions about scale, creative autonomy, and what happens when one of the most technically audacious names in contemporary horology becomes part of the world’s largest luxury conglomerate. LVMH does not disclose financials by brand, but its watch and jewelry division reported revenues of $12.3 billion in 2024 (and for the first nine months of 2025 $8.6 billion), underscoring the magnitude of the platform L’Epée now operates within.

Crucially, Nicolas has remained at the helm of L’Epée, continuing to run the company from its factory in Delémont, in Switzerland’s Jura region near Basel. Under Nicolas, L’Epée has become one of the most technically ambitious names in contemporary clockmaking, producing mechanical table clocks that sit somewhere between engineering experiments and sculptural statements. Since joining LVMH, the brand has continued to expand manufacturing capabilities while maintaining its collaborative ethos, releasing headline projects with Louis Vuitton and unveiling a monumental astronomical clock created with Vacheron Constantin that debuted publicly at the Louvre.

In this wide-ranging conversation with Crown & Caliber’s Editor-in-Chief Alexandra Cheney, Nicolas speaks candidly about operating inside the world’s largest luxury group, the reality of preserving autonomy within a public company, and why he believes L’Epée’s future lies in doubling down on both mechanical audacity and creative risk rather than dilution through scale.

Crown & Caliber: It’s been a minute since we last spoke Arnaud! Congratulations again on being acquired. How’s life under the LVMH umbrella?

Arnaud Nicholas: Oh, Life is good. Life is good. It’s a new challenge. As you know, the company has been bought by LVMH, and Mr. Arnault asked me to remain at the head of the company in order to continue the development that I had generated. We have plenty of projects going on, which is nice. That’s the sexiest part of the business, developing new products, but we are also developing the manufacturing too. When you are independent and you are limited with budget, when you have a group, LVMH behind you, you can put a lot into the development. You don’t have the same relationship with your bank manager. We have had a couple of new launches. In fact, working for the group is quite amazing.

C&C: Why is that?

AN: I hoped it would be like that, but at the beginning, I didn’t think it was possible. The CEO of LVMH really remains with the entrepreneurial spirit. He asked me to work and to see where we go. If we need the group, then the group is there. If not, the group does not step in. It is quite amazing. When they acquired the company, it’s what they told me. I said, “okay, okay, you own the company, I understand.” But after over a year, they are not stepping in.

C&C: I mean, it sounds very dreamy, frankly.

AN: For me, when they told me that I was, “yes, of course. You’re selling me the world, but excuse me, bullshit, because you want to buy the company.” But no, actually, it’s true. It’s really the way they run the business. As the CEO, I am fully empowered, and I do what I want. It’s too amazing.

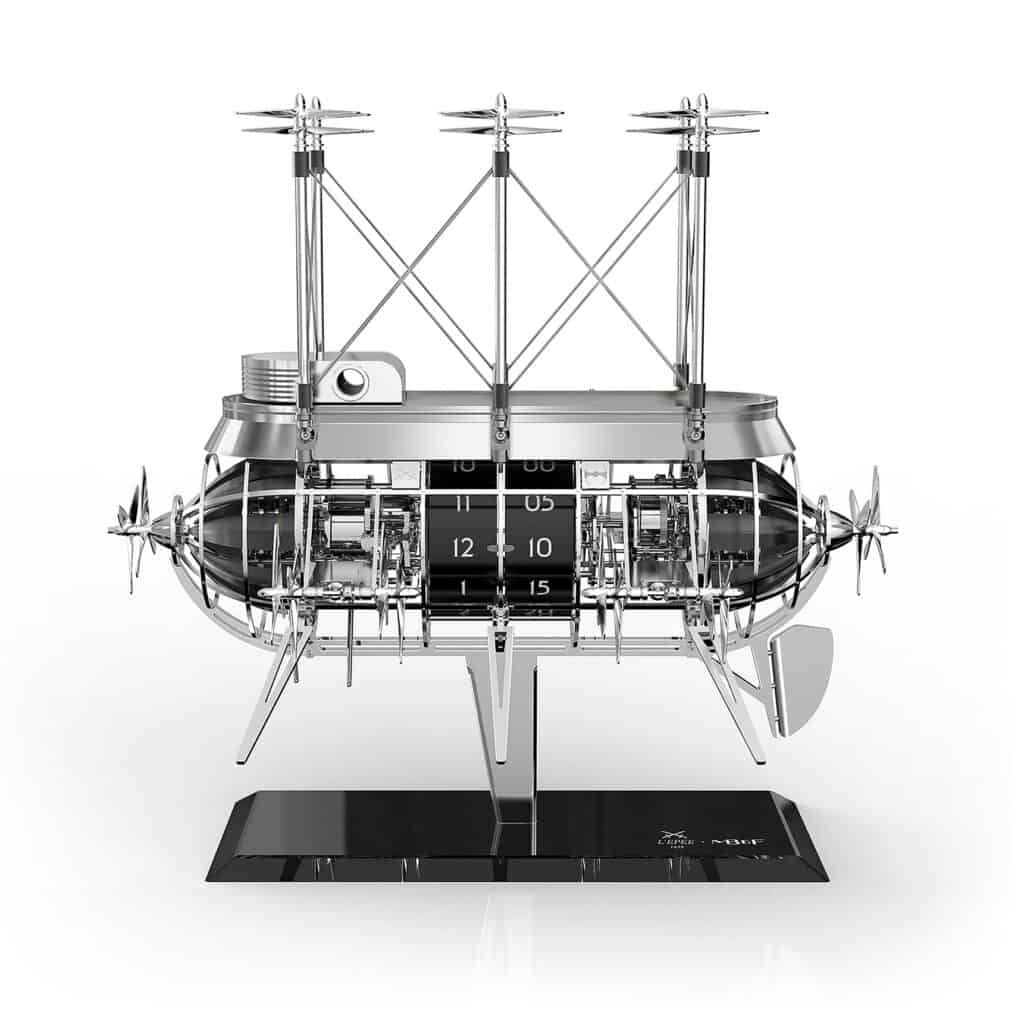

C&C: That is almost too good to be true. At what point do they get involved? L’Epée released the Montgolfière Aéro, a hot-air-balloon-themed table clock in collaboration with Louis Vuitton not five months after LVMH acquired L’Epée.

AN: There’s no obligation for them to work with us. Of course, somehow there is because we are the ones doing these kinds of objects, but there is no pressure on the group to work with one company or another. If it makes more sense to work with a company outside of the group, you work with the company outside of the group. If you think it’s better inside the group, you work with someone in the group.

C&C: It’s just frankly surprising. I mean, it sounds wonderful.

AN: There are challenges. Because you’re part of the group, people assume we will just have plenty of customers. No. At L’Epée, we do both. We have our own brand, but we also work with outside parties. So if I want to work with Louis Vuitton, I have to be better than the others. If I want to work with Tiffany, I have to be better than the others. It’s not only because we are part of the same group, somehow we’re cousins, that where we work together. It makes life a little bit more challenging, but it’s also good, because it gives more motivation. I’m the kind of guy that likes challenges. I like that concept.

C&C: What for you has been trickier? I know you said the relationship with your bank manager is different, but what has been a little bit trickier since being absorbed by LVMH. Is there something that’s become a little more challenging or a little different to navigate?

AN: LVMH is a publicly traded company so we have to manage our image within a publicly traded company. That’s something I was not, I can’t say aware, but I was not really up for that. We had to manage that with our little resources; I was like “okay, guys, I may need some help here to do all the reporting.” So that’s what we did. But that’s about it. It’s a very good thing because I was dreaming for years to be able to build a very nice factory with more machines, basically more investment, but as an indie, you’re not able to do it, because the bank doesn’t follow you. And all of us sudden, it became true. So we have been able to increase our capabilities of production by quite a lot.

C&C: You have a handful over 100 points of sale and have previously said you don’t want to go over 200. How do you add production but keep volume similar?

AN: Mr. Bernard Arnault told us that we should continue the same way of doing the business as I was doing when I was independent, meaning working for my brand a little, working for other brands, working with brands in the group and brands outside of the group. So we continue to supply everyone in the luxury industry that wants to work with us. So we work with (privately owned) Chanel and (Richemont-owned) Vacheron Constantin.

C&C Tell me about the Vacheron Constantin partnership.

AN: It’s something amazing. It’s a clock with an automatum that can make 144 different gestures. The automaton takes the form of a humanistic Astronomer and is choreographed to perform three different sequences, lasting for a minute-and-a-half in total, which can be activated on demand or programmed. It’s part of our DNA to work with those kinds of people. That’s truly our capabilities. As a CEO, I get to decide that.

Also keep in mind, the Louvre never previously exhibited a contemporary product. They made one exception before for dresses, from Dior. Because Mr. Christian Dor has died many years ago. So they were able to, because it was a collection of the years-old fashion, even if some new dresses were also inside. This is the true first time a technical product is shown in the Louvre. That’s amazing. And the product is amazing! It’s 15 patents, 22 complications, over 6,000 components. A basic watch has about 500 components. It’s over three feet tall. We’ve all the detail of a luxury clock that can bear a signature of Vacheron. It’s amazing object already.

C&C: How long did that take you, start to finish, to create?

AN: From the idea to the final product it took us seven years. The first two years we were defining all the concepts, figuring out what we wanted to show off on the inside and outside of this object. What was the philosophy of the object? It was the same way I’m developing any product. We were starting with the history and then we made a product. But it’s so big that it took us three years to figure out the story. But that’s the way we have made it. Working the story first, then designing the engine on the housing at the same time. Exactly what we are doing at L’Epée.

C&C: What is a normal amount of time that an idea will take you from start to finish?

AN: Two to three years. This was more than two times what we are usually doing. But the product is so amazing that, yes, we can understand why it took us so long.

C&C: That means that you were working on this clock before and after you got acquired. How did it change post-LVMH acquisition? Some may say that Richemont Group, which owns Vacheron Constantin, is a competitor to LVMH.

AN: Sure. The competitors are competitors in watches. We are clocks. It’s different. Even after the acquisition, LVMH trusted L’Epée. When I told them that we will remain like an independent company, that they will not see what we are doing, and that they can trust us, they did. They have. So that was quite a proof of confidence between the groups. Once again, the group found out about the product, when it was displayed at the Louvre. Nobody had seen any pictures of drawings or anything about it before then.

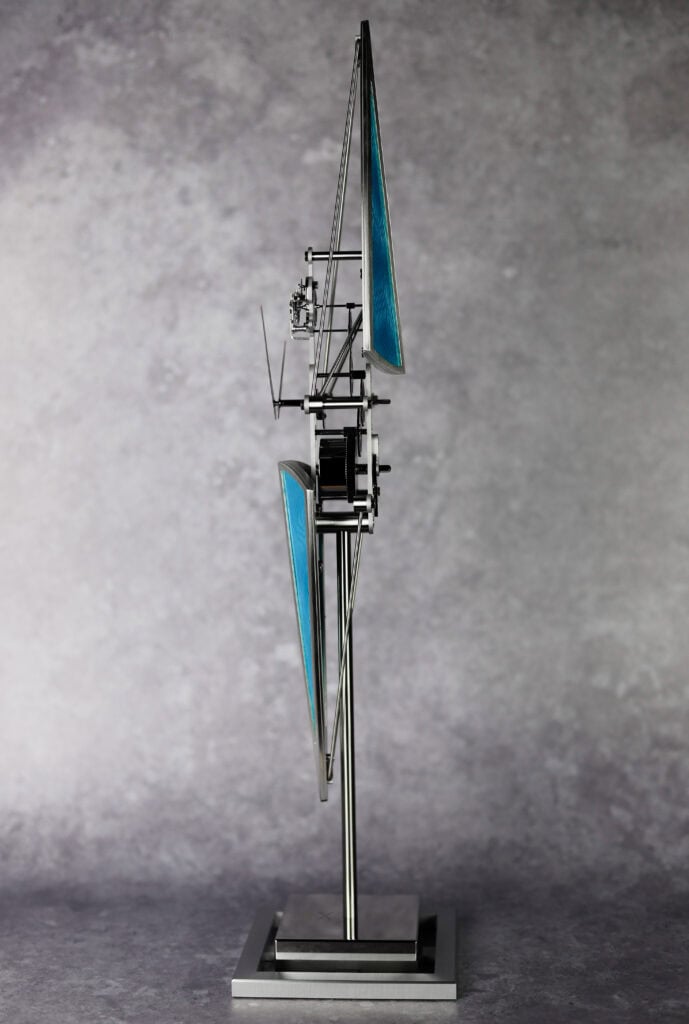

C&C: Talk to me a little bit about your creative art residency.

AN: It’s something I wanted to do for quite a time. When you launch a new product, a fully new product with new shape, new functions, everyone focuses on the new shape. But everyone forgets about the artist who makes it. No one really speaks about them. And for once, we have taken some of our existing products, given them to artists and asked them to create an interpretation. We pick and choose some artists that we have worked with, and every single artist had to work on different pieces. That gave us a very nice portfolio of 20 products from 20 artists. I was able to do that because I had the group behind me.

C&C What do you mean, you were able to do it because you had the group behind you?

AN: We take a big risk doing this. If people don’t like it then you have a problem because you have as many pieces as if you launch a new product. It’s handmade and painted and each one is unique. It’s because I have this freedom with the group that we were able to do that.

C&C: I know one of the things that L’Epée is quite known for is the idea of power and prestige. Your clocks have long been official gifts by governments and influential figures and heads of state and all of those things. How do you balance the seriousness of the carriage clock with this creative art and pop art? How do you remain authentic to where you came from?

AN: In fact, it’s pretty simple. We have followed our DNA. DNA is not a product, it’s not a color, it’s not the shape of a dial. Many people have been doing that for years. L’Epée has always thought about DNA as something much wider. DNA for us is being able to make a luxury product, because we only do a luxury product. In different shapes with creativity, mixing form and functions, and giving something that is playful for the owner. That’s why in the carriage clock, you are able to see through it. On the side, you can see the moment. Something that is fun to use. And that’s from the beginning, Mr. Auguste L’Epée. He established a company on August 1st.

Auguste was a brilliant genius and an engineer. But he was also someone that was quite fun. We decided that it was part of the DNA of the brand. But the creative art, nowadays, is much bigger than the business than the carriage clock.

C&C: As part of a public company are you disclosing how many clocks you’re making each year? Or is that information still private?

AN: Still private. Even within the group, they still don’t know how many products we are making every year. Because it’s a completely confidential object. Confidential elements that we keep for us and the group doesn’t step in. What we get to the group is our revenue and projected revenue, like any other publicly traded company. But we don’t disclose what we are working on, who we are working with, and what kind of product we’re going to lunch. That’s something that we never discuss. The object that we have at the Louvre with Vacheron Constantin, for example, the group found out about it with the press.

C&C: That’s wild.

AN: That part of the deal, that we remain fully ourselves. The group didn’t want to hear about what we’re doing. It was continue to do it, you’re doing what you’re doing pretty well. To be honest, I had to pinch myself a couple of times to be sure that I was awake. Those words came from Mr. Bernaud Arnault. That was even more amazing.

C&C: How did your first conversation with Bernard Arnault begin?

AN: The guy really surprised me. We are a small company within the group. A very small company. But Mr. Bernard Arnault asked me to come to meet him, and we spent half a day speaking together about how I had the idea of making clocks. Why is it a good business? What my idea of continuing the business if I was not acquired. And what is my thinking for a future business. We spoke about that for almost three hours.

When I arrived, a small company like us, when I heard ‘Mr. Arnault would like to meet you, can you come to Paris?’ I was thinking, okay, Arnaud, you’re going up in Paris. Five hours a trip for five minutes in his office. That’s okay. No. Mr. Bernard Arnault was waiting for me in front of the elevator. Not sitting in front of his desk, he was standing at the front of his door, in front of the elevator, waiting for me. I was wow. You know, that’s the kind of person he is. The way he treated me, I cannot realize it. I still have difficulties realizing it.

C&C: That is just the ultimate way to do business, right? Respect and engagement; a lot of people could learn from that right now.

AN: To be honest, a lot of people can learn from him and his behavior. And also, he’s doing business, you know. He has a huge group, but he has a huge group of independent companies. That’s why he’s powerful and why people are afraid of him. Instead of having 10 brains managing the group, he has one brain for each company. Which is much, much more clever. If we were managed by people doing watches, it’s not the same business. It’s close, but it’s a different business. They will make mistakes. And that’s why people are coming to us. They want to make their clocks. It’s because when they try to make clocks inside their own company, and they’re making watches, they don’t know how to sell it. So he’s clever enough to understand that. And by the way, he’s very clever. He’s able to understand that and to let the people who work the way they have worked and to know that company A cannot be managed the same way as company B.

C&C: One of the exciting pieces of news is that next year you are going to be at Watches and Wonders.

AN: Yes. That’s something that it’s beautiful. Okay, it’s very expensive. But I’m able to do it because there’s a group behind me. But yeah, it’s exciting, very exciting.

C&C: How do you even think about preparing for Watches and Wonders? Obviously, I saw you at LVMH Watch Week, and that was a way, way, way smaller version of that. But how do you even plan for that?

AN: We should not lose our philosophy. That’s the more important thing. We are now part of the big time. Don’t lose yourself. That’s for me, that’s what is the most important is we have to have something that is very nice, but we have to keep the same kind of philosophy that we have already have. If we change everything, because we think that now we’re big, we’re to kill the business. So, yes, we are going to prepare something nice, but I don’t want to do something that is overwhelming, because that’s not what we are, you know? Product is the most important. It’s not about marketing, it’s not about originals. It’s about the product. That’s what makes us a little bit successful, and I’m sure that’s why we continue our journey.

C&C: Can you leave us wanting more Arnaud?

AN: We are trying to do new partnerships. We used to dedicate 20 percent of production to collaborations. We want to flip that and have 80 percent collaborations. L’Epée likes to surprise people. We will continue, as we have done, to put the artist up front. Because once again, I really thank them to have helped me to put L’Epée where it is now. You will see products on both sides. One side is the technical aspect; form and function and the other side will be on the artistic field. With our last Creative Art Residency some people did not really get it. They found that we were going a little bit too far. Okay, why not? What is the purpose of a piece of art? It’s to express a message. How do you express a message? It’s by evoking, inspiring or shocking. So some people have been shocked by our latest creations. But they forget what a piece of art is.

C&C: It’s a very good point.

AN: The idea behind it was to give back to what the artist has given us in the past. That was a true idea; some people thought that we were going too far. How can I go too far if I just want to thank my partners? To be honest, I was surprised with that, but okay.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.